Field trip to Aberystwyth and Clarach led by Dr Charlie Bendall August 23rd 2023

Field trip to Aberystwyth and Clarach with Dr Charlie Bendall to investigate sedimentary structures in the Aberystwyth Grits Sunday 20th August 2023

Some of the group on the beach with Charlie Bendall

Our August field trip, led by Dr. Charlie Bendall, followed the coast from Aberystwyth to Clarach. This coast is famous for its sedimentary structures, including "Turbidites". Charlie had provided copious background information on Gravity Flows of all sorts for prior study and, after members assembled at The Castle, he broadly outlined the full range of terrestrial and marine slides, slumps and other gravity movements, often described confusingly by a proliferation of ill or loosely defined terms.

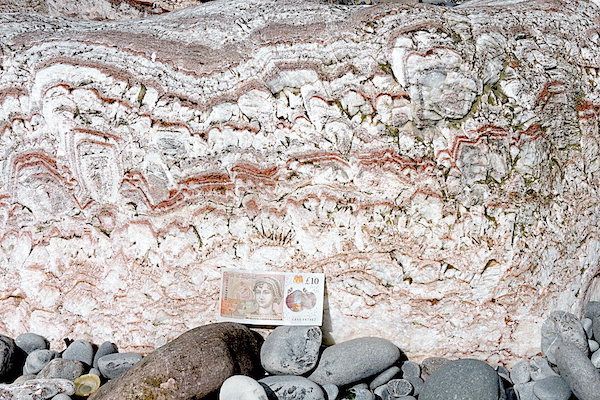

A marked degree of folding at the base of Constitution Hill, Aberystwyth. Charlie explained that there was no evidence that this folding was tectonic in origin. He thought it was an extreme degree of soft sediment deformation before complete lithification.

We then walked down to the first location.

This was a 3m deep cutting below the castle alongside the promenade where a series of thin to medium bedded sandy and silty couplets was exposed. These were good examples of turbidites which could be classified in terms defined by Bouma. They clearly had an erosive base with a normally graded sandy Bouma unit A, grading into a finer unit B with some parallel lamination and a unit C with some cross lamination.

Walking to the north end of the promenade, the cliffs below Constitution Hill expose more Aberystwyth Grits folded in a conspicuous plunging anticline, with associated faulting. The bedding was somewhat thicker here with sandier beds alternating with darker shales.

Alternating sandstone and mudstone beds at the foot of Constitution Hill. Some of the sandstone beds are very thin, hardly disturbing what would otherwise have been a single thick mudstone bed.

Also visible just above the thick basal sandstone unit is a distinct layer of concretions within the overlying mudstone bed

A closer view of the concretions

The second part of the trip was to explore the cliffs north of Clarach. Most of the group took the cliff walk but Bill and I took the easy option of driving and avoiding the long walk back to the car.

An example of soft sediment deformation within a sandstone bed

A small detour took us to the south of the bay where we (probably) located a thin bentonite which had been noted from earlier research. Such beds are the result of volcanic eruptions which distribute ash into the sea over a wide area so they are good marker units for dating.

This bed was not too obvious as it was obscured by a black algal deposit. It also seemed quite hard, but this can happen during diagenesis.

A thick sandstone bed at the Southern end of Clarach Beach showing Bouma A and Bouma B units.

Crossing the bridge over the river, we continued along the beach.

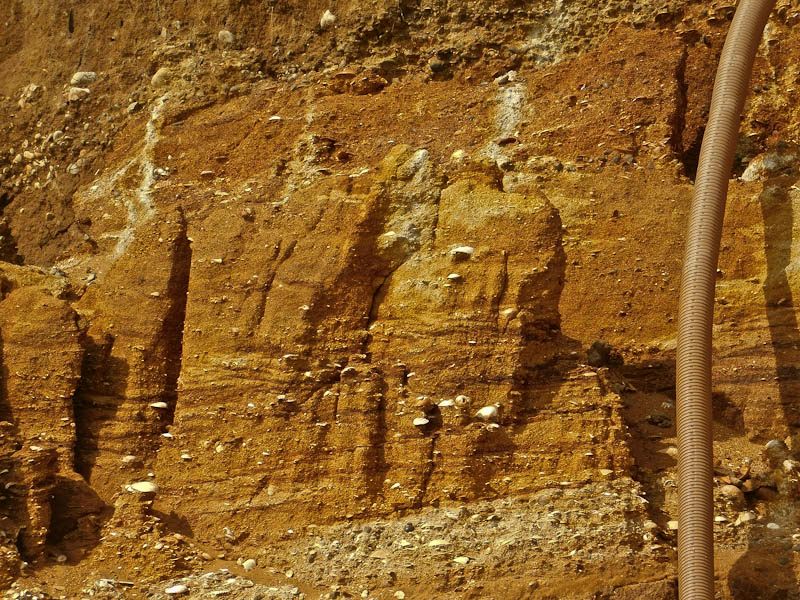

The cliff face underneath the coast path at the Northern end of Clarach.

At the base are beds of the Aberystwyth Grits. Above that is a grey layer, and above that a brown layer. These are both of glacial origin. The grey layer is material arising from Welsh glaciers, while the brown layer is material arising from an Irish glacier. The Irish glaciers eroded rocks with a high iron content, so the brown colouration is a useful marker for glacial material arising from an Irish glacier

As the tide was falling we could clamber round to another inlet and a cave where the undersides of beds could be observed. There flute casts and burrows had been beautifully preserved. In higher beds nearby concretions had developed in a thicker shaley mudstone. The way these develop is not fully understood. Sometimes they start from a visible nucleus, possibly a bit of fossil, but often there is nothing visible. They could start with a crystalline particle which could be at a molecular scale and grow into the surrounding sediment, cementing it and, given space and stable conditions, develop a spherical structure. Interesting forms like "cone-in-cone" can be produced by the complex interaction of crystal growth with sediment particles.

A cone in cone concretion within a sandstone bed at the Northern end of Clarach Beach.

A higher power view of the concretion. (We later discovered a pebble on the beach which was an intact concretion, eroded out of the beach rock by wave action)

A cave at the Northern end of Clarach Beach. The base of the sandstone bed forming the roof of the cave shows prominent flute casts.

An enjoyable trip exploring Aberystwyth Grits, turbidites and Bouma interpretations with an accomplished leader wound up with a cliff walk back to Aberystwyth.

Photos by Chris Simpson and text by Chris Simpson and Tony Thorp