The Geology of Lanzarote by Prof. Cynthis Burek

The Geology of Lanzarote

At our July indoor meeting, Prof. Cynthia Burek gave a talk on "The Geology of Lanzarote."

She is Professor of Geoconservation at the University of Chester; indeed, as far as we know, the only professor of geoconservation! She is a long time friend of our club, having talked to us on several occasions, the last of which was two years ago when she told us about "Geoconservation and the Saltscape Project", outlining conservation of the Cheshire salt industry. Our July talk took us further afield.

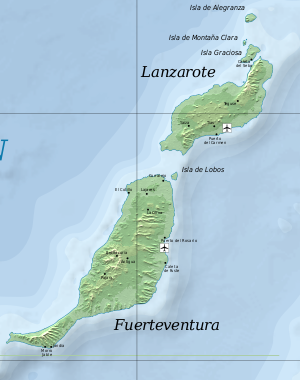

Lanzarote is the northernmost and easternmost of the Canary Islands which all have a volcanic origin the details of which are not at all clear-cut.

Lanzarote and Fuerteventura by map of the canary islands.svg:Mysid, Wiki Commons

Lanzarote and its geologically similar neighbour, Fuertaventura, are the oldest, having some 20Ma of volcanics exposed above sea level. They are separated by a shallow sea and would have been joined together in the Ice Age. Lanzarote has an area of some 300 sq. miles, is just 120 miles off the African coast, has no surface water and has a resident population of 146 000.

It is dominated by two shield volcanoes, Ajaches in the south and Famara in the north which are 20Ma and 10Ma old, lying on ocean basement 50-40Ma. They were originally two separate island volcanoes which were subsequently connected by products from a central rift. They are now much eroded into cliffs and ravines, with the lowlands in between having aeolean sand dunes. Surprisingly, these comprise white sand, not black as would be expected from the surrounding dark basaltic rocks. Hence there is some conjecture about their derivation. A possible source would be from the Sahara, but it seems more likely that they were formed by trade wind drift of sedimentary deposits previously exposed in periods of lower sea level.

There have been two major recent eruptions in the Holocene/Anthropocene, one from 1730 to 1736 and a smaller one in 1824.

The 1730 eruption of Timanfaya was the third largest basaltic fissure eruption of historical times, after Laki (1783AD) and Ejdgja (934AD) in Iceland. It lasted 68 months and produced 700 million cubic metres of lava from over 30 vents. It was the largest Canary Island eruption within the last 500 years.

Lava field in Timanfaya photo creative commons M. Rodríguez

Fortunately reconstruction of the event is helped because there were accounts by eye witnesses, in particular by the parish priest of Yaiza. More recent smaller eruptions have produced a number of craters around the main shield volcanoes.

The 1824 eruption was smaller, lasted three months and was focussed on the Nuevo del Fuego vent in Timanfaya.

Montano del Fuego Timanfaya national park by Norbert Nagel Germany Wiki Commons

Lanzarote's wide central plain is non volcanic and covered by white aeolean sands. It is thought that some 7-5Ma during a period of low sea level the island was covered by biocalcarenite sands including terrestrial gastropods, tortoises and the eggshells of large birds together with fragments of marine fossils and volcanic clasts. Lime dissolved from these shells helped form thick calcretes on top.

There is some controversy over how the islands were formed, it could have been to do with African tectonics as part of the Atlas lineament, or perhaps above a hotspot? The islands are near a zone of Alpine deformation and could be an extension of the Agadir Fault, but no geological or geophysical evidence has been found. Nor does it appear to look like a hotspot because the time/distance relationship looks wrong. If it were moving over a hotspot, like Hawaii, the older islands, like Lanzarote, would be over cooler mantle and would have subsided by now.

A more likely scenario is that it is on a leaky transform fault, like Iceland. In this situation, in addition to the strike-slip motion, there is some extensional movement tending to open the fault, allowing melt to leak through, producing new crust.

The most influencial geologists to study the island were Juan Carlos Carracedo who worked for 40 years and published some 200 articles and Valentin R. Troll.

Perhaps the island's most famous inhabitant was Cesar Manrique, a Spanish artist, sculptor, architect and activist who lived there. He prodused sculptures which grace public spaces and left his extraordinary house, built within the volcano, to the Cesar Manriques Foundation. He influenced planning policy which strictly opposes high rise concrete. He died in a car accident in 1992 aged 73.

Strangely, for an island with no surface water, viticulture is a major industry, with vines cultivated on the rich volcanic soil and watered from condensed dew. Because of the large diurnal temperature variation, condensation occurs on stone protective walls erected round each vine.

Vineyards in La Geria, photo creative commons

The area has been declared a Global Biosphere Reserve, containing the Timanfaya National Park, two nature parks, reserves, and SSSIs. Together with the island of Chinijo, it is part of a UNESCO Global Geopark which comprises a significant territory with a heritage and supporting programme. It involves geotourism, engages the local inhabitants and also fosters experiment and research to enhance its geological heritage. The locals have apparently taken "ownership" of the project and assist by policing the concept.

Altogether it was an interesting evening, perhaps inspiring some of us to visit and explore the island; "flygskam" permitting of course!