Introduction to Outer Hebrides Geology

Introduction to Outer Hebrides Geology by Chris Simpson secretary of MWGC.

This talk is based on a guided trip round the Hebrides led by Chris Darmon and Colin Scofield from geosupplies (http://www.geosupplies.co.uk)

We took the ferry from Oban to the island of Barra at the southern end of the Hebrides. Then we worked our way north along the whole chain of islands, finally getting the ferry back from Stornoway to Skye. We had eight nights, staying at four different hotels. There was a lot of geology to see; and also, a lot of interesting non-geological sites such as the Calanais Stones – a Neolithic site erected around 2,900BC.

The islands are mainly composed of very old rocks including the oldest rocks seen in the UK. The following is a brief summary of the main aspects of Hebridean geology.

3Ba: first terrains formed, divided by faults between the islands.

2.8Ba: first metamorphosis to give predominantly meta-igneous rocks – the Badcallion event.

2.4Ba: widespread invasion by basaltic Scourie dykes.

? Age: second metamorphosis – re-worked the gneiss and converted the basaltic dykes into meta-basaltic dykes.

1.8 – 1.7Ba: pegmatitic dyke invasion.

~400Ma: Caledonian Orogeny which created the Outer Isles Thrust Fault.

The typical appearance of much of the island chain. Gneiss weathers to produce poor soil – so bare rock is very common.

The Outer Hebrides Thrust Fault is a major factor behind the geomorphology of nearly the whole island chain, being around 100 miles long. Most of the island rocks are gneiss in one form or another. Recent research is managing to differentiate the gneiss into different terrains; and also providing evidence of the precursor rock before it was metamorphosed into gneiss.

Sandstone, granite and basalt will all end up as gneiss if subjected to high-grade metamorphism – but they will retain the geochemistry of the original rock, especially the trace element geochemistry. So even after three billion years, we can still say that one area of gneiss came from Mid-Ocean-Ridge basalt, while another area of gneiss came from sandstone.

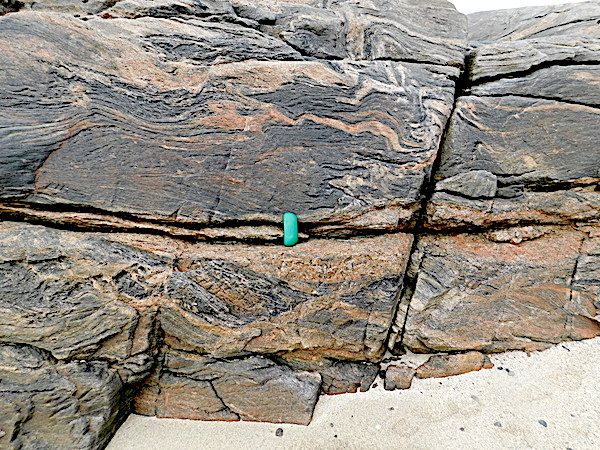

Banded gneiss. The appearance varies greatly from one area of the Hebrides to another, both in the shape and colour of the banding. There is no such thing as “typical” gneiss. (The scale is the green spectacles case.)

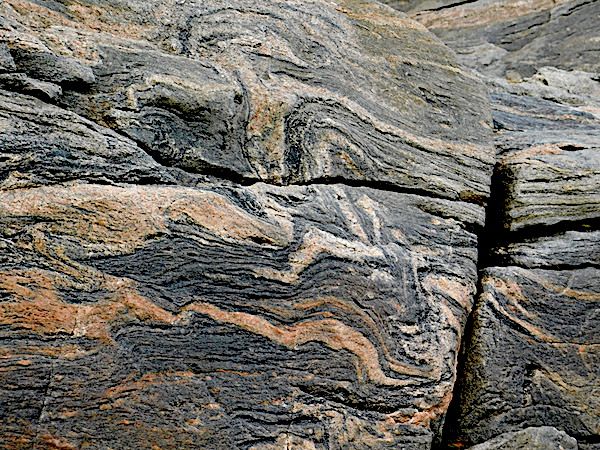

A closer view of the upper central part of the above photo

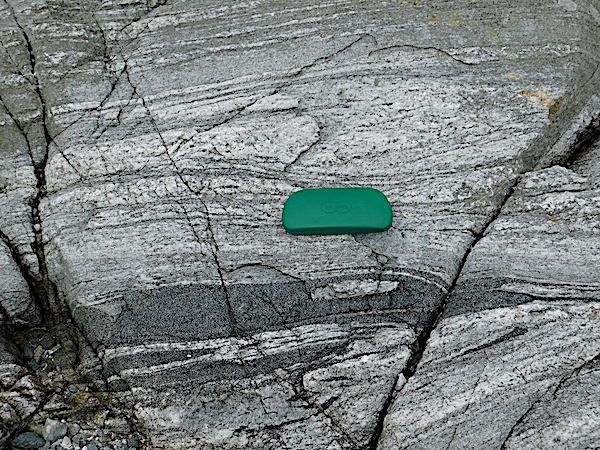

Increasingly complex gneiss banding.

Absolutely chaotic gneiss

Larger-scale banding and chaos.(Fence posts at the top of the picture give a scale.)

A recent dyke related to the Skye super-event approx 65Ma.The scale is an A6 field notebook

A pegmatitic dyke with huge quartz crystals.

On the geology map, this area is described as crushed gneiss and pegmatitic dykes near where thrust planes split.

A road cutting where the Outer Hebrides Thrust fault runs. The fault line runs diagonally from the top near the left down to the bottom at the centre. All the rock to the right of that line is disorganised

A closer view view of the fault boundary.

The thrust fault on another island. Here it is nearly horizontal with a more obvious contrast between the top and bottom layers.

The Calanais Stones on the island of Lewis, 12miles west of Stornoway.

Many of the stones are composed of banded gneiss. (The scale is a camera lens cap.)

Text and photos Chris Simpson